Potentially life-threatening emergency

Pneumonic plague

Alerts and Notices

Important News & Links

Synopsis

Infection with the gram-negative bacillus Yersinia pestis can lead to a highly lethal disease, commonly referred to as the plague, that requires early recognition and prompt treatment. The pneumonic form of plague is characterized by a severe and rapidly progressive pneumonia. Yersinia pestis infection can also manifest as bubonic and septicemic forms.

The reservoir for Y pestis is most commonly rodents (eg, prairie dogs, squirrels, chipmunks, rats), although cases involving dogs and cats have been described as well. The vectors are fleas that feed on the infected animals and then can transmit the bacteria to susceptible hosts such as humans.

Pneumonic plague has both a primary and a secondary form. The primary form is contracted from inhaling aerosolized droplets from an infected person and occurs in only about 3% of plague-infected patients. Secondary pneumonic plague occurs with infection beginning outside of the lungs such as progression from bubonic or septicemic plague to the lungs; approximately 12% of such cases progress to pneumonic form. Bubonic and septicemic plague are rarely transmissible from human to human but may become transmissible via droplets once in the pneumonic stage.

The incubation period can range from 1-6 days (average 2-4 days), and the pneumonic form can be transmitted person to person via droplets through direct, close contact.

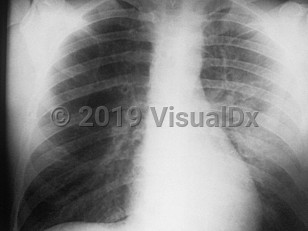

Pneumonic plague results in a severe fulminant illness with high fever, chills, headache, productive cough, chest pain, hemoptysis, extreme malaise, myalgias, tachypnea, tachycardia, and pneumonia. Gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea are also commonly seen. If not treated within 24 hours of onset, pneumonic plague rapidly progresses to acral cyanosis, respiratory failure, septicemia, circulatory collapse, and death. Untreated, the mortality rate of pneumonic plague approaches 100%. With treatment, the rate is as low as 16%.

It is important to recognize that initial symptoms may be similar to more common causes of pneumonia, and the clinician must have a high index of suspicion based on endemic locations, recent travel, and close contact with rodents or domestic animals that have recently become sick. Initial diagnosis in the emergency department for a single case may be difficult. Unless the link to exposure is readily apparent, most cases will be diagnosed after admission based on culture data (sputum or blood). Human-to-human transmission is possible, so if pneumonic plague is suspected, infection control practices must be rapidly implemented. Control measures and personal protective equipment for health care workers should be geared toward droplet transmission at a minimum. Consult infection control experts to determine whether additional protection is warranted for caring for patients with potential aerosolizing interventions (eg, high-flow nasal cannula supplemental oxygen delivery).

Endemic plague is seen in the southwestern United States (Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and California). Cases of plague also continue to be reported in much of sub-Saharan Africa, parts of South America, and Asia. The incidence is likely higher than reported given that the majority of cases happen in underdeveloped regions of the world where reporting mechanisms are lacking. Naturally occurring pneumonic plague is uncommon. Hikers, campers, veterinarians, and owners of infected animals, especially those living or visiting endemic areas, are at higher risk for contracting plague.

Pneumonic plague is classified as a Category A bioterrorism agent because of its ease of dissemination, contagiousness, and high mortality rate. The most likely method of dispersal would be as an aerosol, but simply having an infected individual walk around infecting others is another possible mode of dissemination, albeit less efficient at making many persons ill. Concern for bioterrorism should be triggered if multiple patients arrive with similar symptoms.

Rapid patient isolation, use of personal protective equipment for health care workers, antibiotic delivery, and notification of public health professionals are essential preliminary steps when the disease is suspected. If bioterrorism is suspected, the clinician should have a low threshold to activate the hospital incident command system and notify public health authorities.

If the outbreak is intentional and pneumonic plague is occurring in the community, all patients with rapidly progressive pneumonia should be considered to have pneumonic plague unless an alternate diagnosis is found.

The reservoir for Y pestis is most commonly rodents (eg, prairie dogs, squirrels, chipmunks, rats), although cases involving dogs and cats have been described as well. The vectors are fleas that feed on the infected animals and then can transmit the bacteria to susceptible hosts such as humans.

Pneumonic plague has both a primary and a secondary form. The primary form is contracted from inhaling aerosolized droplets from an infected person and occurs in only about 3% of plague-infected patients. Secondary pneumonic plague occurs with infection beginning outside of the lungs such as progression from bubonic or septicemic plague to the lungs; approximately 12% of such cases progress to pneumonic form. Bubonic and septicemic plague are rarely transmissible from human to human but may become transmissible via droplets once in the pneumonic stage.

The incubation period can range from 1-6 days (average 2-4 days), and the pneumonic form can be transmitted person to person via droplets through direct, close contact.

Pneumonic plague results in a severe fulminant illness with high fever, chills, headache, productive cough, chest pain, hemoptysis, extreme malaise, myalgias, tachypnea, tachycardia, and pneumonia. Gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea are also commonly seen. If not treated within 24 hours of onset, pneumonic plague rapidly progresses to acral cyanosis, respiratory failure, septicemia, circulatory collapse, and death. Untreated, the mortality rate of pneumonic plague approaches 100%. With treatment, the rate is as low as 16%.

It is important to recognize that initial symptoms may be similar to more common causes of pneumonia, and the clinician must have a high index of suspicion based on endemic locations, recent travel, and close contact with rodents or domestic animals that have recently become sick. Initial diagnosis in the emergency department for a single case may be difficult. Unless the link to exposure is readily apparent, most cases will be diagnosed after admission based on culture data (sputum or blood). Human-to-human transmission is possible, so if pneumonic plague is suspected, infection control practices must be rapidly implemented. Control measures and personal protective equipment for health care workers should be geared toward droplet transmission at a minimum. Consult infection control experts to determine whether additional protection is warranted for caring for patients with potential aerosolizing interventions (eg, high-flow nasal cannula supplemental oxygen delivery).

Endemic plague is seen in the southwestern United States (Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and California). Cases of plague also continue to be reported in much of sub-Saharan Africa, parts of South America, and Asia. The incidence is likely higher than reported given that the majority of cases happen in underdeveloped regions of the world where reporting mechanisms are lacking. Naturally occurring pneumonic plague is uncommon. Hikers, campers, veterinarians, and owners of infected animals, especially those living or visiting endemic areas, are at higher risk for contracting plague.

Pneumonic plague is classified as a Category A bioterrorism agent because of its ease of dissemination, contagiousness, and high mortality rate. The most likely method of dispersal would be as an aerosol, but simply having an infected individual walk around infecting others is another possible mode of dissemination, albeit less efficient at making many persons ill. Concern for bioterrorism should be triggered if multiple patients arrive with similar symptoms.

Rapid patient isolation, use of personal protective equipment for health care workers, antibiotic delivery, and notification of public health professionals are essential preliminary steps when the disease is suspected. If bioterrorism is suspected, the clinician should have a low threshold to activate the hospital incident command system and notify public health authorities.

If the outbreak is intentional and pneumonic plague is occurring in the community, all patients with rapidly progressive pneumonia should be considered to have pneumonic plague unless an alternate diagnosis is found.

Codes

ICD10CM:

A20.2 – Pneumonic plague

SNOMEDCT:

38976008 – Pneumonic plague

A20.2 – Pneumonic plague

SNOMEDCT:

38976008 – Pneumonic plague

Look For

Subscription Required

Diagnostic Pearls

Subscription Required

Differential Diagnosis & Pitfalls

To perform a comparison, select diagnoses from the classic differential

Subscription Required

Best Tests

Subscription Required

Management Pearls

Subscription Required

Therapy

Subscription Required

References

Subscription Required

Last Reviewed:01/22/2017

Last Updated:08/05/2021

Last Updated:08/05/2021