For patients presenting with hemodynamic instability of peritoneal signs:

- Resuscitate with intravenous (IV) fluids and vasopressors as needed.

- Initiate empiric antibiotics with enteric coverage.

- Engage consultants early, including general and vascular surgery.

- Interventional radiology may also play an important role in treatment for some etiologies of mesenteric ischemia.

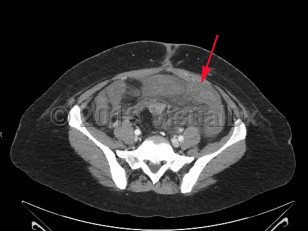

Acute mesenteric ischemia is a sudden interruption or severe reduction in blood flow to the bowel leading to ischemia, necrosis, and ultimately perforation. It is a medical emergency requiring emergent intervention to restore perfusion, often requiring a multidisciplinary approach. Mesenteric ischemia can result from several distinct pathologic entities including embolic disease, arterial thrombosis, mesenteric vein thrombosis, and lack of perfusion due to low flow states or nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI).

Embolic disease most commonly affects the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), largely due to anatomic factors. The SMA branches off the aorta at a 45 degree angle, and rapidly tapers, providing a funnel-like shape that traps emboli. The SMA serves a large area of the bowel from the duodenum through the first two-thirds of the transverse colon, producing profound injury in the setting of acute loss of perfusion.

Mesenteric ischemia is relatively rare with an incidence of roughly 5-8 per 100 000 per year. The incidence of mesenteric ischemia increases significantly with age, with a median age at presentation of 67 years. While advancements in treatment strategies have made significant improvements in the mortality of mesenteric ischemia, it remains high at approximately 50%. As with overall incidence, mortality increases significantly with age.

Patient presentation is characterized by the sudden onset of severe abdominal pain with a benign abdominal examination, often referred to as "pain out of proportion to exam." Many patients will develop vomiting and diarrhea. Bloody diarrhea due to bowel necrosis is a late finding. In occlusive disease, symptoms progress rapidly over hours to days. Those with thrombotic disease may report weeks to months of preceding symptoms suggestive of chronic mesenteric ischemia. These can include abdominal pain worsened after eating (so-called "intestinal angina"), fear of eating, and weight loss. Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia is often observed in the setting of critical illness. Worsening acidosis, hemodynamic instability, feeding intolerance, diarrhea, and abdominal distention are all worrisome signs.

Risk factors for mesenteric ischemia reflect the pathophysiologic mechanisms for each variant: SMA embolism, SMA thrombosis, mesenteric vein thrombosis, and NOMI. Commonly associated conditions include underlying cardiac disease (ie, atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, valvular disorders), hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, smoking, and hypercoagulable states. More rarely, those who have undergone recent endovascular aortic repair are at increased risk.